Undiscovered Ethiopia

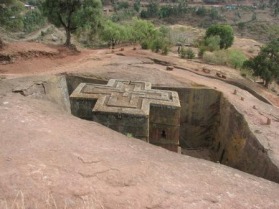

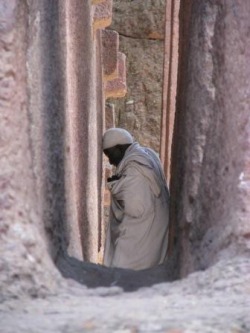

We arose early and made the short trip to the site of Bet Giyorgis. Approaching on foot, we reached the ridge overlooking the church and came upon a remarkable sight. The cross-shaped church, which had been carved as a monolithic rock into the hillside ground in Lalibela, was surrounded by white-robed worshippers who had descended upon here from all over the town to celebrate the feast day of St. George to whom the church was dedicated. Some sat praying on the hillside overlooking the church but most headed down through the labyrinth of narrow passageways to be blessed by the priests in the church courtyard below. We joined them, privileged to be allowed to witness and partake in the ceremony and attracting surprisingly little attention for a bunch of brightly dressed faranjis. Save for the microphone used by the priest for his chanting, it was a scene that had probably changed little in centuries.

For people of my generation, Ethiopia has a particular resonance as the first international crisis to enter our consciousness, our first glimpse at “the world outside our window”. Twenty-five years have passed since the famine that brought the country to the world’s attention and made it synonymous with parched desert, drought and starvation. As the slow and steady progress towards economic and democratic development that has occurred since holds little interest to the western media, this impression remains, certainly judging from the reactions I got when telling people I was going to visit Ethiopia. I wanted to see the country for what it really was in the 21st century, dispel the lingering images of famine and see what it has to offer to visitors.

The socialist dictatorship that bore much responsibility for the effects of the famine was finally overthrown in 1991 and a democratic constitution adopted in 1994. Ethiopia remains a very poor country however with a burgeoning population that makes it difficult to improve living standards and makes food security an issue in a country susceptible to droughts. It also suffers from being located in a very rough neighbourhood. It had a futile and bloody border war with Eritrea in the late 1990s and the exact border demarcation remains a contentious issue. To the west lies Sudan with the Darfur crisis while on its eastern border Somalia is the quintessential failed state. Even its usually stable southern neighbour Kenya experienced post-election riots and violence last year. Nevertheless Ethiopia is making some progress in economic development and a nascent tourist industry is an important part of this.

The socialist dictatorship that bore much responsibility for the effects of the famine was finally overthrown in 1991 and a democratic constitution adopted in 1994. Ethiopia remains a very poor country however with a burgeoning population that makes it difficult to improve living standards and makes food security an issue in a country susceptible to droughts. It also suffers from being located in a very rough neighbourhood. It had a futile and bloody border war with Eritrea in the late 1990s and the exact border demarcation remains a contentious issue. To the west lies Sudan with the Darfur crisis while on its eastern border Somalia is the quintessential failed state. Even its usually stable southern neighbour Kenya experienced post-election riots and violence last year. Nevertheless Ethiopia is making some progress in economic development and a nascent tourist industry is an important part of this.

Ceremony in St. George's Cathedral

Our tour started in the capital Addis Ababa, a vibrant but ragged city of over 3 million people. Founded in the late 19th century, Addis is fairly impressive as African cities go. It is a major diplomatic hub, the African Union is headquartered here, and has large shopping areas in the Piazza and the much rawer experience of the Mercato, one of Africa’s largest markets. Streets congested with the ubiquitous blue and white minivan buses and taxis and numerous building sites with the characteristic wooden branch scaffolding point to a renewed economic vitality. Our first stop was the excellent National Museum, a compact but well presented display of Ethiopian history from ancient fossils to modern artwork. Its most famous exhibit is a replica of Lucy, a 3.5 million year old fossilised skeleton discovered locally in 1973, which was one of the missing links in tracing human evolution. We then visited St. George’s Cathedral, the oldest in Addis and site of the coronation of recent emperors where we were fortunate to witness some religious singing and a ceremony for the recently deceased. This was our first introduction to the importance of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, especially in the north of the country. Ethiopia was one of the first countries to adopt Christianity (in the 4th century) but it has developed into a unique church due to its isolation for many centuries and the influence of ancient Jewish customs. Aside from the famous rock churches of Lalibela, the 17th century Debre Birhan Selassie in Gonder and the island monasteries of Lake Tana are just some of the other beautiful and ornately decorated historical churches in Ethiopia.

Location of the Ark

Ethiopia is a country with a long and unique history, much of which is not generally known to outsiders. As important as the accepted historical narrative however are the traditional Ethiopian legends which, whilst lacking in real archaeological evidence, are just as important to the Ethiopian people and to understanding the country. Perhaps the most significant and colourful of these beliefs involves the Ark of the Covenant, believed by Ethiopians to be located in the northern town of Axum, and the story of how it came to Ethiopia. According to this legend, Queen Makeda, who ruled Ethiopia and Yemen in the 10th century BC, was in fact the biblical Queen of Sheba who visited King Solomon in Jerusalem and bore him a son called Menelik. After being raised in Ethiopia, Menelik returned to Jerusalem aged 22 and spent three years learning the laws of Moses before returning home, accompanied by thousands of Solomon’s followers and, after being told in a dream to take it with him, the Ark of the Covenant. Ethiopians believe that the Ark today resides in the an outbuilding of the Cathedral of St. Mary of Zion in Axum but it is accessible to no-one except the official guardian. Replicas of the tablets reside in every Ethiopian church and are their most protected and sacred item.

This legend is also the basis for the traditional explanation of the centuries old Jewish population in Ethiopia, the Falasha Jews, though this is disputed by more orthodox accounts. Today only a handful remain, as most Ethiopian Jews were airlifted to Israel in the 1980s and 1990s. The Falasha village just outside Gonder is one of the few remnants of this community. Though now populated by non-Jews, the village contains a small stone circular synagogue topped with an iron-cast Star of David and is a poignant symbol of a dispersed culture.

Dongar Palace

Regardless of the historical accuracy of the Menelik legend, it is at the very least a wonderful story and a great insight into Ethiopian culture. It’s worth noting as well that relatively little archaeological work has been done in Axum, so much detail remains to be discovered. Interestingly one of the ruins we visited was Dongar Palace, known by locals as the Queen of Sheba Palace, which comprises the excavated and renovated walls of a 50-room structure. French studies in the 1950s dated the structure to the 7th century AD, dismissing any links to the Queen of Sheba. But, as our guide enthusiastically explained, more recent analysis suggests that this palace had been built on the remains of another one, several centuries older. Archaeologists producing evidence supporting the traditional beliefs become very popular with the local population.

Obelisk of Axum

Aside from its importance to Ethiopian legend, Axum was the capital of the Axumite Empire which flourished in this region from roughly 100BC to 700AD. The Axumites traded with Rome, India and Persia and it was one of the most prominent civilisations of its day. The Axumite kings, who claimed to be descended from Menelik (the Solomonic dynasty extended to Haile Selassie in the 20th century, though with questionable validity) have left many reminders of their reigns, most notably in the stelae field in the centre of town. There are more than 75 of these engraved granite obelisks, some of which were erected to mark the tombs of dead kings. The most impressive is the Obelisk of Axum, 24m high, which was carved from a single monolith of granite rock and somehow transported to the site from 4km away. When the Italian fascist regime occupied Ethiopia in the 1930s, they cut the stele into 3 pieces and transported it to Rome. It was only in 2005 that the structure was finally returned to Axum amid much fanfare and erected back in its original position.

Despite its importance in Ethiopian history (and as the main centre for the Ethiopian Orthodox Church), Axum today is a small, regional town. It’s quite a charming and colourful place however, its main avenue lined by palm trees, brightly painted buildings and vivid red, purple and orange-flowered trees and shrubs. The town makes for very pleasant strolling, browsing the numerous souvenir shops which specialise in religious artefacts like Axumite crosses and traditional robes and scarves. Axum is also a good spot to experience the local culture and nightlife. Ethiopian food is yet another unexpected revelation and we had an excellent meal at a traditional restaurant in town. The dishes are based around injera, a pancake-like carbohydrate with a foam-rubber texture and sour taste which is eaten with a variety of spicy sauces and stews, a unique and delicious cuisine. Later on we hit a few of the town’s bars, including the intriguingly named Cultural Cottage, to sample the local beer.

Whilst Axum is the most important religious and historical centre in Ethiopia, Lalibela is without doubt the country’s most extraordinary and magical site. The rock-hewn churches of the town, carved out the ground, hillsides and cliff faces in the 12th century are remarkable in their conception, construction and detail. When the seven new wonders of the world were recently announced, Lalibela was inexplicably and shamefully overlooked but has since taken on the unofficial title of the 8th wonder.

We flew into Lalibela on an Ethiopian Airlines Fokker 50 propeller plane, landing on an airstrip 25km from the town, the closest suitable area given the mountainous nature of the region. Until recently the only way to reach Lalibela was several days of overland travel on poor roads. Though it is now becoming more accessible to tourists, there are still a mere 60,000 visitors a year, incredible considering the nature of the site. We drove along the winding, mountainous road to the town, past rural scenes of children shepherding goats and farmers ploughing the parched landscapes in anticipation of the rainy season. The church complexes are in the centre of town, divided into two main groups with the cross-shaped Bet Giyorgis further to the south. The intention of King Lalibela, who oversaw their construction, was to create a new Jerusalem in Ethiopia with the two clusters representing heaven and Jerusalem - the stream that flows between them is called the River Jordan and an overlooking hill has been named Mount Sinai.

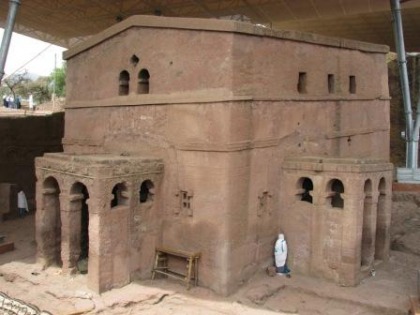

All the churches except Bet Giyorgis have been covered by a protective roof to save the structures from rain and sun erosion but this only marginally detracts from the experience. Each church is of a unique design, most carved out of a single monolith of rock with extraordinary detail in the outside engravings, windows, inner rooms, chambers and columns. Over the next two days we explored each of the buildings, climbing through the labyrinth of tunnels and passageways that connect them. The north-western cluster seems to be part of a planned complex of churches, each carved into the ground and surrounded by courtyards and high walls. It includes Bet Medhane Alem, the largest monolithic rock-hewn church in the world built like a classical Greek temple surrounded by columns and Bet Maryam which contains an interior column supposedly inscribed with details of how the churches were created and how the world will end. Alas, like the Ark in Axum, this is covered and hidden from outsiders. The south-eastern cluster is more varied and less elaborately constructed, comprising both monoliths and cave churches.

What made Lalibela particularly special was that it didn’t feel like visiting a normal tourist site with the usual crowds and commercialism. We were the only western tourists we saw there over two days and the churches are still very much in everyday use, with priests praying and singing in the churches and courtyards, worshippers attending services and making pilgrimages to the site and even pre-school children sitting in one courtyard practising the Amharic and English alphabet. The town itself is also inimitable, feeling barely encroached by the modern world in its remote mountain setting. It’s inevitable I suppose that as tourist numbers to the town increase, the experience for visitors and locals alike will change and restrictions will need to be made on what is accessible. For now though, Lalibela must be one of the most extraordinary yet least visited historical sites in the world.

After exploring the historical sites of Axum and Lalibela, it was time for a change of scenery so we headed to the Simien Mountains for a couple of days of trekking in the National Park. Driving to Debark, the town closest to the National Park’s entrance, we passed many deprived country villages highlighting the poverty of much of the population as well as remnants of the war with Eritrea in the form of refugee camps and abandoned tanks on the roadside. At Debark, we stocked up on supplies and collected the armed guides that are compulsory for trekking in the mountains before making our way to the campsite that would be our base for the next two days.

Gelada baboons

The Simien Mountains are regarded as one of Africa’s premier trekking destinations and it’s easy to see why. The scenery along the trekking routes is spectacular with dramatic peaks, huge gorges and panoramic views across the landscape from atop the escarpment that bisects the park. The area combines features of canyon terrains with alpine-like hills and valleys. Although we visited at the height of the dry season, the greenness of the landscape was still striking with the tree-covered mountainsides providing yet another contrast between the myth and reality of Ethiopia. While there we encountered several troops of Gelada baboons, distinctive shaggy-haired primates endemic to Ethiopia, but the Walia ibex and Ethiopian wolf proved elusive.

The other major natural attraction in northern Ethiopia is the Blue Nile Falls. The Blue Nile River originates in Lake Tana before heading westwards to converge with the White Nile in Khartoum. 30km from where it exits the lake at Bahir Dar, the Blue Nile forms a 45m waterfall known locally as Tis Abay or the Smoke of the Nile. A recently constructed hydroelectric plant as well as the lack of rain when we visited reduced the volume of the Falls with water falling over only a small portion of the 400m cliff. Nevertheless it is still an impressive site and the journey there adds to the appeal. After crossing the river upstream by boat, we walked through fields before a break in the trees revealed the Falls in the distance. We then descended down to the river to appreciate the power of the waterfall and feel the spray in our faces, feeling almost reminiscent of 19th explorers discovering Africa!

If Ethiopia hadn’t offered enough surprises already, the former capital of Gonder was to top it off. Perhaps the last thing you would expect in the Horn of Africa is a medieval castle but the Royal Enclosure in the centre of town has a whole complex of castles and related buildings. Built by King Fasilidas and his successors from the 17th century onwards, the Gonderian architecture of the structures reveals Arab, Indian and European influences but they were built by Ethiopians after the kingdom entered a phase of isolation. The enclosure is well preserved and maintained and wonderful for strolling around amongst the castles, ruins and cages used to house the Emperors’ black lions.

Travelling in Ethiopia is an exercise in challenging preconceptions and confounding expectations. The country has a historical heritage unparalleled in sub-Saharan Africa and a diverse and beautiful landscape at odds with the desert image that blights it. In an increasingly homogenous world, Ethiopia is unique – the only African country never to have been colonised with a culture, historical and contemporary, unlike anywhere else. Negative impressions caused by famine and war have kept visitors away so for now it is a holy grail for travellers – an extraordinary country barely touched with tourists. Experience it while this lasts.

To see more of Ethiopia, check out my Blurb book